The target of an ideal cooperative truth-seeking process of argumentation is reality.

The target of an actual political allegedly-truth-seeking process of argumentation is a social reality.

Just as knowledge of reality lets you predict what will happen in reality and what cooperative truthseeking argumentation processes will converge to, knowledge of social reality is required to predict what actual argumentation processes will converge to. What will fly in the social court.

I think there is a common buckets error from conflating reality and social reality.

Technically, social reality is part of reality. That doesn’t mean you can anticipate correctly by “just thinking about reality”.

Putting reality in the social reality slot in your brain means you believe and anticipate wrongly. Because that map is true which “reflects” the territory, and what it means to “reflect” is about how the stuff the map belongs to decodes it and does things with it.

Say you have chained deep enough with thoughts in your own head, that you have gone through the demarcation break-points where the truth-seeking process is adjusted by what is defensible. You glimpsed beyond the veil, and know a divergence of social reality from reality. Say you are a teenager, and you have just had a horrifying thought. Meat is made of animals. Like, not animals that died of natural causes. People killed those animals to get their flesh. Animals have feelings (probably). And society isn’t doing anything to stop this. People know this, and they are choosing to eat their flesh. People do not care about beings with feelings nearly as much as they pretend to. Or if they do, it’s not connected to their actions.

Social reality is that your family are good people. If you point out to a good person that they are doing something horribly wrong, they will verify it, and then change their actions.

For the sake of all that is good, you decide to stop eating flesh. And you will confront your family about this. The truth must be heard. The killing must stop.

What do you expect will happen? Do you expect your family will stop eating flesh too? Do you expect you will be able to win an argument that they are not good people? Do you expect you will win an argument that you are making the right choice?

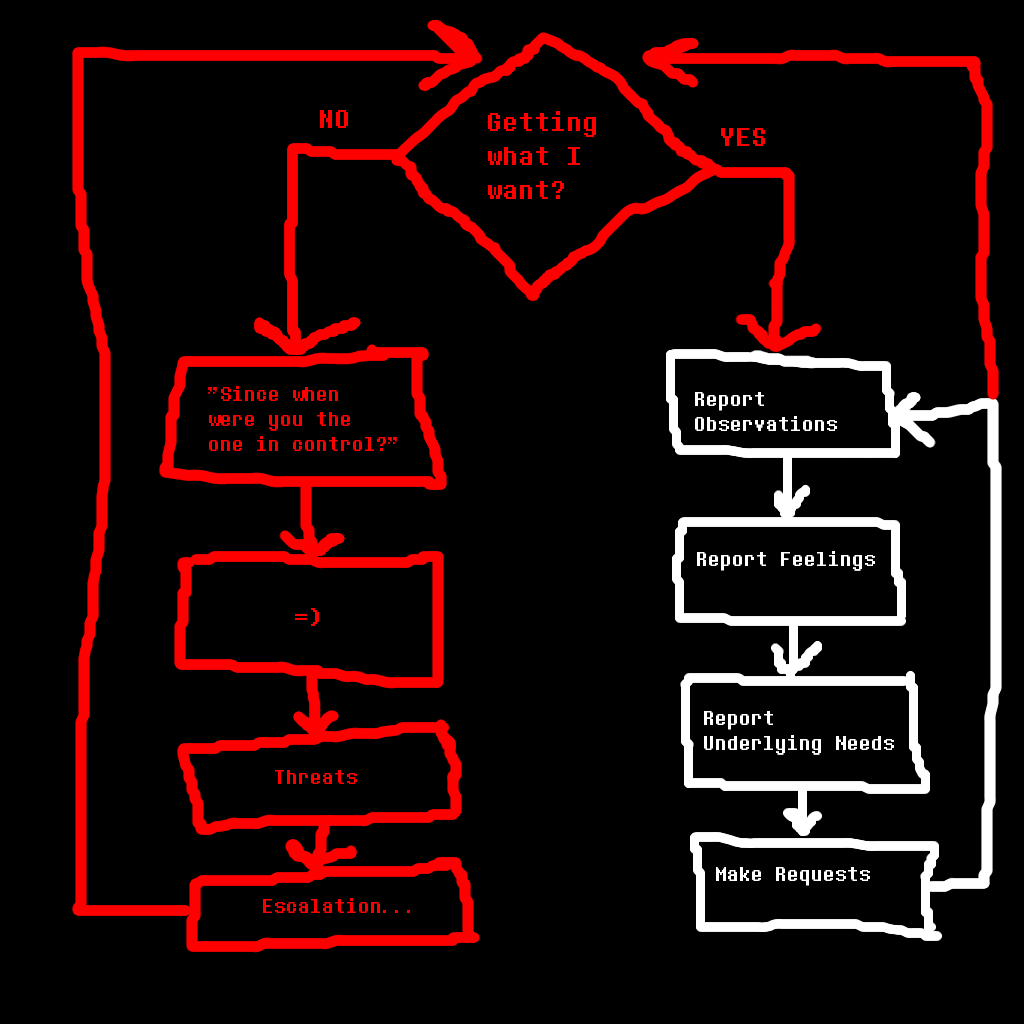

“Winning an argument” is about what people think, and think people think, and think they can get away with pretending with a small threat to the pretense that they are good and rational people, and with what their false faces think they can get away with pretending.

So when everyone else’s incentives for pretending are aligned toward shifting social reality away from reality, and they all know this, and the fraction of good-rational-person-pretense which is what you think of them is small and can be contained in you because everyone’s incentives are aligned against yours, then they will win the argument with whatever ridiculous confabulations they need. Maybe there will be some uncertainty at first, if they have not played this game over vegetarianism before. As their puppetmasters go through iterations of the Russian spy game with each other and discover that they all value convenience, taste, possible health benefits, and non-weirdness over avoiding killing some beings with feelings, they will be able to trust each other not to pounce on each other if they use less and less reality-connected arguments. They will form a united front and gaslight you.

Did you notice what I said there, “ridiculous confabulations”?

ri·dic·u·lous

rəˈdikyələs/

adjective

deserving or inviting derision or mockery; absurd.

You see how deep the buckets error is, that a word for “leaves us vulnerable to social attack” is also used for “plainly false”, and you probably don’t know exactly which one you’re thinking when you say it?

So you must verbally acknowledge that they are good rational people or lose social capital as one of those “crazy vegans”. But you are a mutant or something and you can’t bring yourself to kill animals to eat them, People will ask you about this, wondering if you are going to try and prosecute them for what you perceive as their wrong actions.

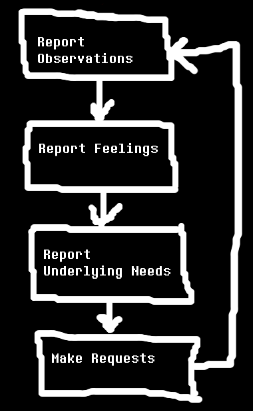

“My vegetarianism is a personal choice”. That’s the truce that says, “I settle and will not pursue you in the social court of the pretense, ‘we are all good people and will listen to arguments that we are doing wrong with intent to correct any wrong we are doing’.”.

But do you actually believe that good people could take the actions that everyone around you is taking?

Make a buckets error where your map of reality overwrites your map of social reality, and you have the “infuriating perspective”, typified by less-cunning activists and people new to their forbidden truths. “No, it is not ‘a personal choice’, which means people can’t hide from the truth. I can call people out and win arguments”.

Make a buckets error where your map of social reality overwrites your map of reality, and you have the “dehumanizing perspective” of someone who is a vegetarian for ethical reasons but believes truly feels it when they say “it’s a personal choice”, the atheist who respects religion-the-proposition, to some extent the trans person who feels the gender presentation they want would be truly out of line…

But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.

Learn to deeply track the two as separate, and you have the “isolating perspective”. It is isolating to let it entirely into your soul, the knowledge that “people are good and rational” is pretense.

I think these cluster with “Clueless”, “Loser”, and “Sociopath”, in that order.

In practice, I think for every forbidden truth someone knows, they will be somewhere in a triangle between these three points. They can be mixed, but it will always be infuriating and/or dehumanizing and/or isolating to know a forbidden truth. Yeah, maybe you can escape all 3 by convincing other people, but then it’s not a forbidden truth, anymore. What do you feel like in the mean time?

Father has promised

Father has promised